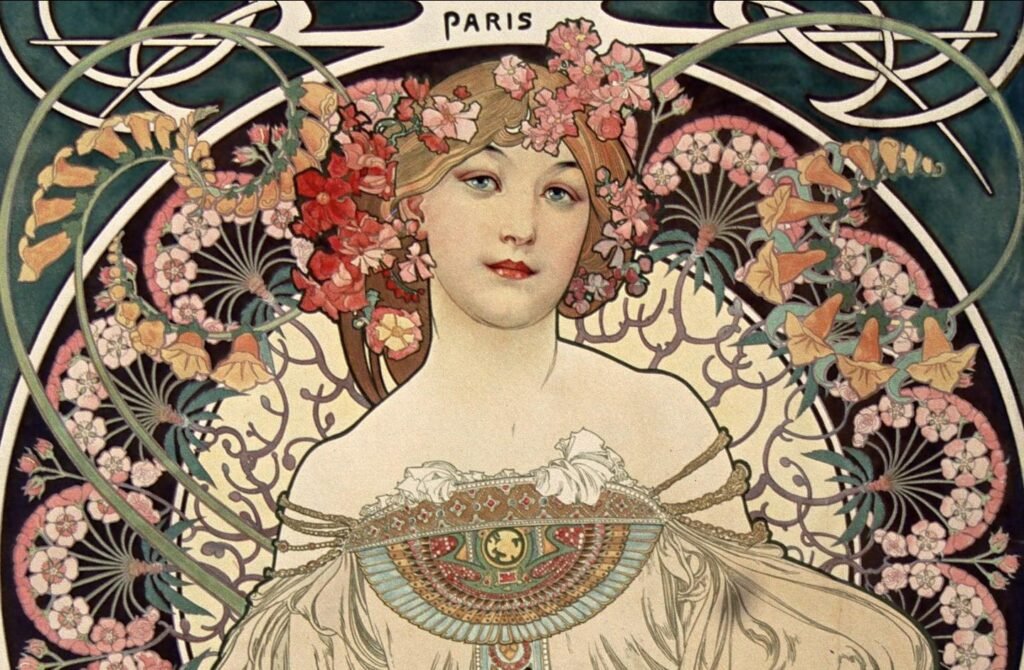

Art did innovate. It curved. It bloomed. So, it enchanted storefronts, wedding invitations, liquor bottles, and metro stations. From Paris to Prague, from Alphonse Mucha to Hector Guimard, Art Nouveau became Europe’s last great ornamental breath before collapse. It was an organic, sensitive art, devoted to the curve — and, above all, silent.

At the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, everything seemed to promise lightness. Progress had become the new myth. Trains crossed continents, electric lights banished darkness, and tearooms sparkled like bourgeois cathedrals. Art Nouveau dressed this world in arabesques and fluid lines, selling an illusion of continuity and harmony. It was as if nature had finally been tamed by the hands of taste and technique.

Yet all ornament hides a disguise. Behind the translucent stained glass and sinuous furniture, what truly moved was capital. Art Nouveau was less a revolt against mass production than an effort to mask it with elegance. William Morris wanted art for everyone; his successors preferred it framed in gold and signed. What posed as innovation was, often, recycled luxury for a bored elite trying to pretend they still felt something when faced with beauty.

Art Nouveau: The Rupture Between Decorative Dream and Brutal History

That Belle Époque — which today would better suit the sterilized aesthetic of DALL·E (an AI that generates visually pleasant, yet often artificial and generic images) than the social reality of its time — was a collective illusion. An ornamented fantasy of stability. And like every European fantasy, it ended in a trench.

When the bayonets, tanks, and poison gas arrived, no arabesque survived. The soft curves of Art Nouveau were crushed by the right angles of industrial war. Mucha’s posters faded beneath the wail of sirens. The silence of contemplation gave way to the roar of machine guns. You don’t paint stained glass in the middle of an artillery barrage.

Art Nouveau, with its promise of total beauty, revealed itself as what it had been all along: a gilded screen before the abyss. It was an art that dreamed of the eternal and stumbled into the real.

Did it innovate? Perhaps. But as camouflage. As carefully applied makeup before a public execution. True rupture didn’t come from ornament. It came from the blast. From the mud. From the dry sound of modernity baring its teeth.

In the end, art innovated — but history smirked and pulled the trigger.