Arte Povera was born in Turin, Italy, in 1967, through the critic Germano Celant, who gathered a group of artists interested in questioning commodity and mass production logic.

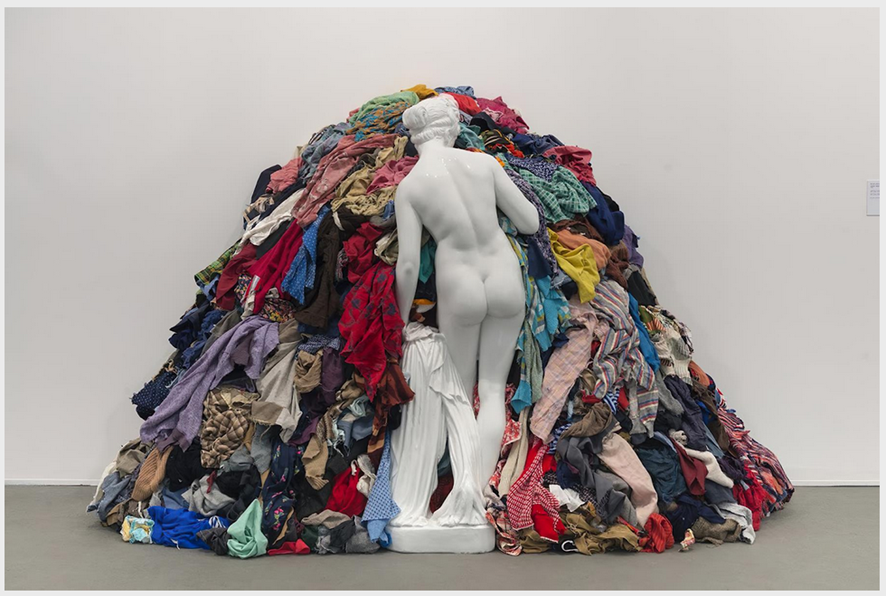

Instead of painted canvases or classical sculptures, they used “poor” materials — earth, stone, paper, logs, rust, used fabrics, and even industrial scrap.

The goal was to emphasize raw material and process, recovering an almost ritual dimension of artistic creation. In its early manifestations, Arte Povera rejected the cold objecthood of American minimalism and proposed works that grew in situ, transformed over time, or referenced ancestral poetics.

Among the central figures of this movement, besides Alighiero Boetti and Mario Merz, Michelangelo Pistoletto stands out for his decisive contribution to the conceptual expansion of the movement.

Michelangelo Pistoletto and a New Form of Art

Michelangelo Pistoletto (born in 1933 in Biella) gained international recognition with his Mirror Paintings, created from 1962 onwards.

In these, the artist covered mirrored metal surfaces with fragments of pictorial images so that the viewer, approaching, sees themselves reflected and simultaneously inserted into an open and mutable composition.

This strategy dissolves the traditional boundary between artwork and audience, turning participation into a plastic element. In the following decades, Pistoletto expanded his range of actions to community performances, urban interventions, and the concept of the Third Paradise, presented in 2003.

The idea of the Third Paradise proposes a balanced fusion between the Natural Paradise (first stage) and the Artificial Paradise (second, technological stage), establishing a new model in which human creativity reassumes ecological and social functions.

Material, Sustainability, and Contemporary Art

Today, Arte Povera’s proposals resonate in many debates. These include sustainability, circular economy, and relational art. Using discarded materials anticipates modern practices. These include upcycling and community art. They aim to reinsert waste into the creative cycle.

Pistoletto’s Mirror Paintings prefigure our digital culture. They foreshadow social networks and online interaction. The focus shifts from passive contemplation. It moves to the audience’s active participation. This audience creates meaning in real time.

The Third Paradise echoes current concerns. It addresses balancing technology and planetary limits. It also inspires collaborative projects. In them, communities integrate art, science, and activism.

We see installations in contemporary art spaces. They recover the processual side of Arte Povera. So, they use roots, ashes, and collected plastics. They even use open-source software. These materials generate sculpture and performance.

Galleries adopt the “open laboratory” format. Visitors are invited to plant seeds. They can dig through piles of earth. They can also interact with electronic sensors. This continues the Povera ethos directly. This ethos involves both the body and the environment.

The Contemporary Relevance of the Arte Povera

In summary, Arte Povera emerges as a manifesto against the objectification of art and remains alive today by inspiring practices that value unpredictability, cooperation, and dialogue between humans, matter, and technology.

Pistoletto’s legacy — with its emphasis on participation, reflection on the human condition, and reconciliation between nature and technology — provides a visionary protocol for 21st-century art, inviting us to reinvent, with every gesture, the space where we live and create.