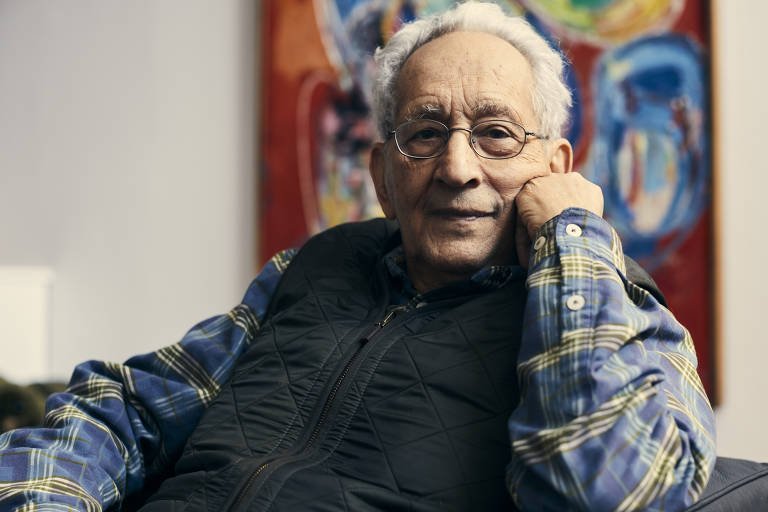

Frank Stella radically transformed the concept of painting by expanding it beyond the flat surface. His work challenged the limits of the traditional canvas and pushed abstract art into a new phase—one that is more dynamic, volumetric, and spatial.

From his early minimalist pieces to his monumental and colorful structures, Stella guided painting toward the realm of sculpture, without ever abandoning its pictorial essence. Over the decades, his work evolved alongside the key debates of contemporary art.

He was one of the first artists to understand that painting could be both an object and an action. In doing so, he reinvented not only the language of art but also the way audiences move through and react to a work.

Frank Stella and Painting as Structure: The End of Illusion in Abstract Art

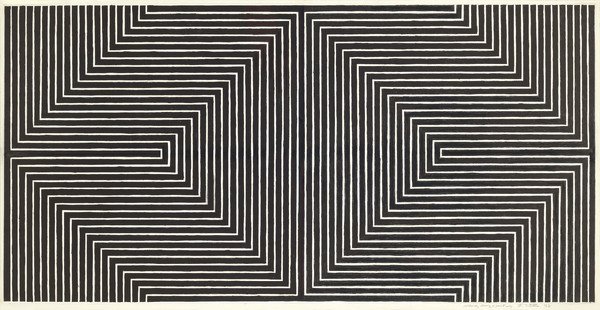

When Frank Stella exhibited his Black Paintings series in the late 1950s, viewers were confronted with an entirely new vision. Instead of expressive brushstrokes or emotional compositions, the canvases were made up of symmetrical black stripes, outlined by thin, uniform lines.

There was no depth, no figure, no narrative. Painting asserted itself as pure surface. In his own words: “What you see is what you see” (Stella, 1966). This statement became one of the defining mantras of minimalist painting.

The Black Paintings completely rejected illusion. The canvas was no longer a window—it became an object. According to the study The Birth of Shaped Canvas by Princeton University (2022), Stella played a decisive role in the development of the so-called shaped canvas, a support that broke away from the rectangular format to assume precise geometric contours. By doing this, the artist began to sculpt the painting itself, turning it into volume.

Still in the 1960s, Stella produced series such as Irregular Polygons and Protractor Series, intensifying the use of angular shapes and vibrant colors. Though these works remained flat, they carried an expansive energy. Color was no longer a background—it became structure. The canvas gained rhythm, almost choreographing the viewer’s gaze.

Stella’s transition was closely followed by critics and theorists of the time. According to Columbia University (2021), his works were seen as a bridge between minimalism and formal expressionism, because although formally rigorous, they carried an impulse of expansion that related to the body and to space.

From the Flat to the Three-Dimensional: Painting That Moves, Art That Breathes

By the late 1970s, Stella had fully abandoned any trace of two-dimensionality. His series such as Exotic Birds and Polish Village introduced relief, layering, and sculpture.

Painting unfolded into folded surfaces, metallic tubes, colored aluminum, and visual fragments that extended into the physical space. The artwork was now built like a living organism—articulated, complex, and almost baroque.

This phase of Stella’s work was deeply influenced by his engagement with architecture and music. In Working Space (1986), a book in which he reflects on the legacy of European painting, Stella argues that space should be conquered by painting, not merely represented.

When referencing Caravaggio, for example, he suggests that the spatial drama of classical works can be translated into abstract language through volume and gestural composition.

According to the study Painting in Three Dimensions by the University of Oxford (2023), Stella’s three-dimensional expansion of painting sparked debate among critics. It challenged the modernist dogma of medium purity. However, the artist himself rejected such constraints.

For Stella, painting was free to merge with sculpture, design, and even engineering. This is demonstrated by his large-scale works created with digital technology in the 1990s and 2000s.

By integrating movement, color, and structure, Stella created works that force viewers to walk around them. They observe from multiple angles and perceive how light and time alter the aesthetic experience.

His painting became spatial choreography—not a fixed point on the wall, but an environment. A painting that breathes and pulses. In a world saturated with digital images, Frank Stella’s art remains a powerful reminder of the physical and emotional force of the artistic object in real space.