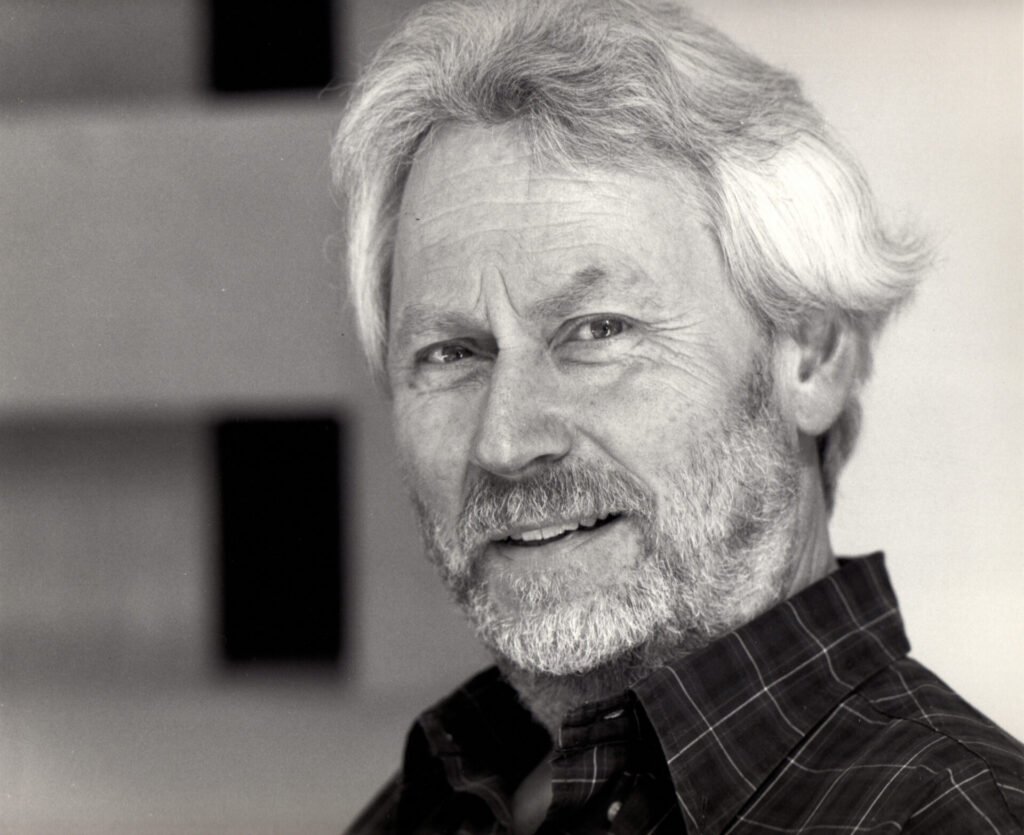

Gerhard Richter, whose artistic trajectory lies between photography and abstraction, pioneered a creative model in which chance and tools act not as mere instruments, but as active components of the aesthetic process.

From his early monochromes with loose brushstrokes to radically transformed photographic series, Richter sustains a constant dialogue between gesture and contingency. As a result, he breaks with the idea that painting should obey an illusion of absolute control.

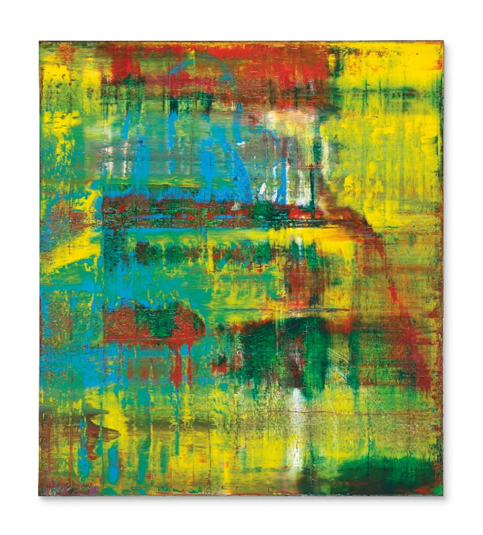

At the core of this practice is the use of the squeegee, spatula, and scalpel. Gerhard Richter applies them not to impose predetermined forms, but rather to generate unpredictable textures and fractures. As he drags the squeegee—a tool inspired by screen printing—across successive paint layers, the artist exposes and removes underlying colors, turning each motion into a unique and unrepeatable event.

This method, highlighted in the curation of the Museum Barberini, avoids aiming for a “finished” result. Instead, it captures moments when the paint’s material reveals the support’s internal tensions.

The Role of Chance and Gesture in Richter’s Art

Consequently, chance emerges as an inevitable partner in this technical approach. By integrating randomness—whether a slip of the squeegee or the uneven spread of pigment—Gerhard Richter creates a dialogue between human gesture and the painting’s response. In this context, what appears to be a mistake becomes essential raw material.

Ortrud Westheider and Dietmar Elger observe that Richter, by incorporating chance in a calculated way, relinquishes conscious control over the painting process. This principle challenges the long-standing tradition that links artistic virtuosity to technical precision. It also opens up space for a viewer-led reconstruction of an always-incomplete visual event.

In curatorial discussions, Hans Ulrich Obrist emphasizes the relational experience of the audience when facing such unstable surfaces. Monochrome mirrors and chromatic gaps project the viewer into an architectural space where the artwork fragments before itself.

This focus on “intermedia”—the friction zone between painting, photography, and performance—places the visitor in the role of co-protagonist. Each shift in light and each crack of color evokes a fragmented narrative, urging the observer to continuously reinterpret the meaning of the artwork.

Gerhard Richter: A Laboratory of Contemporary Art

Gerhard Richter thus inaugurates an artistic ethos in which tools gain autonomy and chance becomes institutionalized as a poetic agent. Far from being a romantic gesture, this is a rigorous and paradoxical formal program.

The artist arranges paint layers as successive memory records, purposefully crossed by flaws. This conception has influenced newer generations and redefined the role of painting in contemporary art, transforming the studio into a conceptual experimentation lab.

Therefore, Richter’s method shows that contemporary art is not defined merely by its finished form, but rather by the dynamic architecture of its ruptures. It is in this encounter between tool and chance that a singular poetics emerges.

Painting becomes an evolving event, inviting us to reflect not only on what we see, but on how and why something reveals itself before us—always renewed in its essential imperfection.