Japanese Modernism represents one of the most unique and refined interpretations of modernism in the twentieth century.

While Western movements leaned toward industrial functionalism and an aggressive break with the past, Japanese artists and architects proposed a silent modernity, deeply rooted in millenary traditions. Lightness, time, and emptiness became central concepts for the aesthetic renewal of Japanese art in the post-war era.

More than a style, Japanese Modernism was a cultural response to the collective trauma caused by war and the rapid modernization of the country. It sought forms that could integrate technological innovation and spiritual contemplation.

Thus, tradition ceased to be denied and began to directly dialogue with the present.

Japanese Modernism and Tradition as Structure: The New Born from the Old

Unlike European modernism, marked by the rejection of the past, Japanese Modernism chose a hybrid path: incorporating tradition as an essential part of the modern experience.

Elements such as the use of wood, the appreciation of negative space (ma), and respect for the natural cycle of time were re-signified. Instead of creating a rupture, the movement established bridges between centuries of Japanese art and the new aesthetic language of the twentieth century.

One landmark of this transition was the work of architect Kenzo Tange, winner of the Pritzker Prize in 1987. His work reconciled Western rationalism with the spirit of ancestral Japan. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial building (1955) exemplifies this fusion: concrete and glass coexist with poetic voids and suspended structures.

According to a study by the University of Tokyo (2020), Tange transformed the principles of international modernism by integrating them with the logic of the Japanese pavilion, which prioritizes flow and visual permeability.

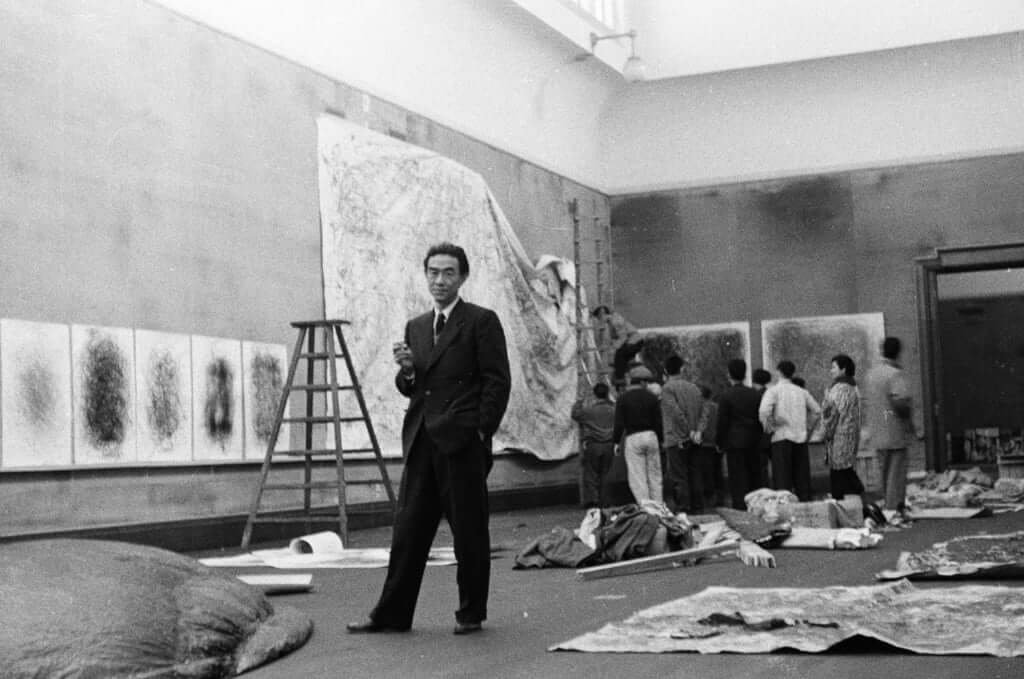

In art, movements such as Gutai, founded in 1954, reconfigured the modern gesture with Eastern philosophical references. Artists like Kazuo Shiraga and Atsuko Tanaka used the body, chance, and ephemerality as means to challenge Western painting conventions.

According to the study From Calligraphy to Performance: The Gutai Group Reconsidered by Harvard University (2021), this group was essential in putting Japanese art on the international map. They did this without abandoning its spiritual and poetic roots.

This perspective also influenced graphic design, contemporary ceramics, and landscaping. In all these fields, the notion of balance—between fullness and emptiness, light and shadow, sound and silence—was redefined through minimalist solutions that reveal a profound awareness of time.

Lightness, Impermanence, and the Aesthetic of the Ephemeral

In Japanese Modernism, lightness is not merely a formal attribute. It is, above all, a philosophical stance. Influenced by Zen Buddhism and Taoist thought, this movement values the transient, the unfinished, the imperfect.

Unlike Western monumentality, modern Japanese works seek delicacy and the absence of excess. It is a modernity that whispers rather than shouts.

This thought is present, for example, in the work of Isamu Noguchi, the Japanese-American sculptor and designer. He created pieces that seem to float in space. His Akari lamp series (started in the 1950s) is a synthesis of this ideal: rice paper, bamboo, and organic forms produce soft and atmospheric light.

According to research by the Yale University Art Gallery in 2022, Noguchi was decisive in consolidating a modern Japanese aesthetic that combined art, utility, and sensitivity.

Moreover, the use of time as an aesthetic material is recurrent. Many modern Japanese artists and architects designed works that transform with the passing seasons, light, or shadow. Tadao Ando’s architecture, for example, although later than the classical modernist period, is a direct heir to this tradition.

His exposed concrete constructions reveal the lightness of space by the way they shape light. The Church of the Light (1989), although minimalist, is deeply spiritual.

This temporal dimension also appears in the relationship with nature. Contemporary Japanese gardens maintain the tradition of simulating impermanence. Each season brings a new visual reading. The landscape becomes a work in motion.

In times marked by acceleration and noise, Japanese Modernism offers a radical alternative: to build the new with silence, lightness, and respect for time.