Latin art is more than aesthetic expression. It is political strength, identity construction, and a visual record of centuries of resistance. In every stroke, color, or composition, a unique way of interpreting the world reveals itself.Not from colonial imposition, but from the lived experiences of bodies, territories, and memories that inhabit Latin America.

More than representing cultures, art produced in the Latin American continent denounces silencing, questions hegemonic narratives, and reaffirms belonging.

Therefore, it is not just about appreciating artworks but understanding the historical and social context that sustains them. Latin art pulses with contradictions, mixing, and above all, resistance.

From Ancestry to Protest: Roots Projected into the Present

From the revolutionary Mexican murals to contemporary graffiti in São Paulo’s peripheries, Latin art has always been marked by strong social engagement.

During the twentieth century, artists such as Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros transformed walls into stages for popular and anti-imperialist narratives. These murals were not mere urban decorations: they were visual declarations of struggle and national iden”tity.

According to a study by the University of Texas at Austin (2021), Mexican muralism was one of the first forms of public art to challenge elites. It directly engaged with the people, using images as tools of political education.

This heritage remains alive in various Latin American contexts, where art continues to be a vehicle for denunciation, welcome, and transformation.

Latin art also intertwines with religious practices, indigenous rituals, and Afro-diasporic languages. The Peruvian artist Elena Tejada-Herrera, for example, uses Andean textiles and ceremonial elements in her performative installations, uniting ancestral femininity with contemporary critique.

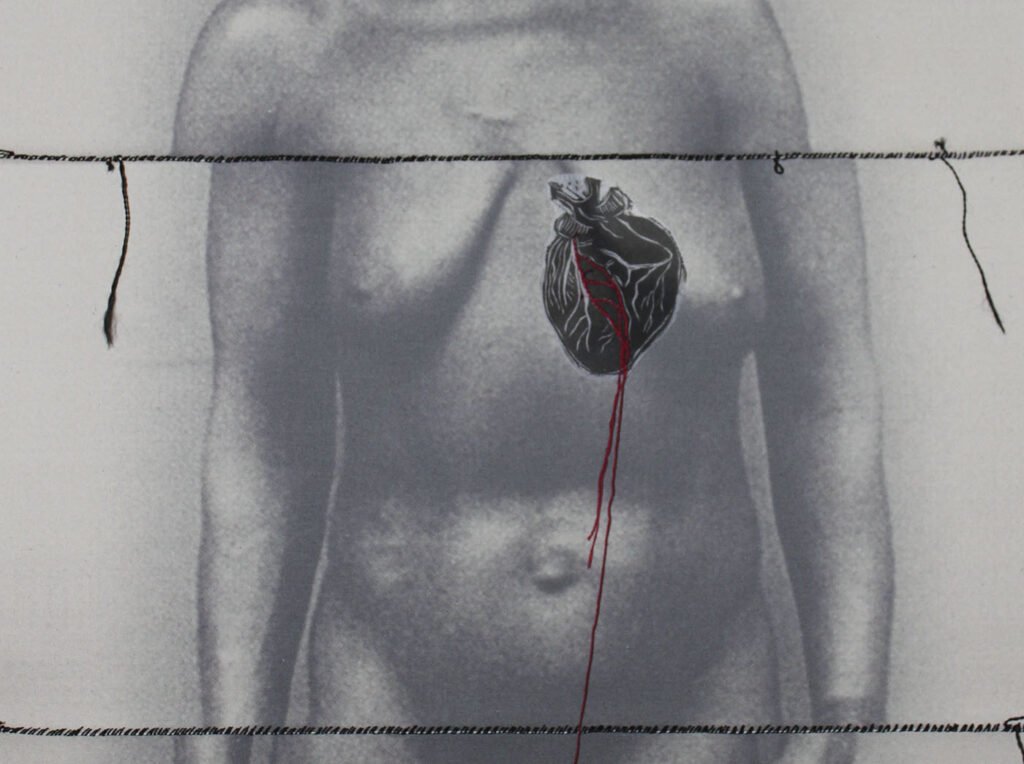

Meanwhile, Brazilian artist Rosana Paulino rescues memories of slavery and black women in series such as Assentamento (2013). She uses sewing, photography, and drawing as forms of healing and re-signification.

“Assentamento” by Rosana Paulino, 2013

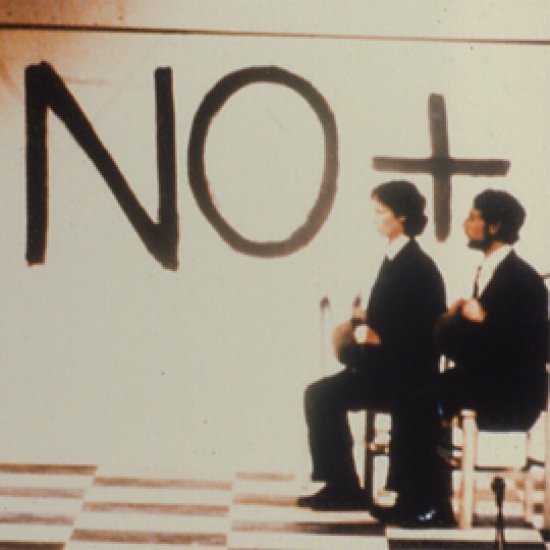

Collectives like CADA (Chile) or 3Nós3 (Brazil) used urban performances and interventions to bypass censorship and keep political debate alive.

As pointed out by the study Visual Resistance in Latin America from the University of California, Berkeley (2022), this kind of production consolidated one of Latin art’s central traits: its ability to survive even in the most adverse contexts.

Latin Art: Colors That Shout, Images That Heal

Chromatic intensity is one of the most recognizable visual marks of Latin art. Vibrant reds, deep blues, lush greens; the colors here are not merely decorative but carry symbolism, memory, and emotion.

They evoke the continent’s exuberant nature, indigenous and African traditions, and popular festivities. But they also evoke the pain of absences, the blood of struggles, and institutional violence.

This symbolic charge transforms each artwork into political territory. Artists such as Beatriz González (Colombia), Teresa Margolles (Mexico), and Tania Bruguera (Cuba) engage directly with issues like state violence, forced disappearances, femicides, and censorship.

Their works often use everyday objects: furniture, clothing, bodies, to question the normalization of violence and mobilize the viewer.

According to research from Columbia University (2020), Latin art operates as a counter-archive. Instead of repeating official records, it builds other memories, from subaltern voices and collective experiences.

This is visible, for example, in the practices of Mapuche artists in Chile, who rescue indigenous worldviews as forms of cultural resistance.

Another important trait lies in the valuation of the body and performance. Many Latin artists work with ephemeral actions, urban occupations, and sensory experiences, understanding the body as a territory of resistance.

Argentine artist Marta Minujín, known for her monumental and performative works, stated that “art should not be static; it must move with the people.”

Latin Art in The New World

In the contemporary field, collectives like Mujeres Creando (Bolivia), MAHKU (Brazil), and Las Tesis (Chile) expanded this repertoire, promoting the intersection between art, activism, and pedagogy. Latin art thus continues to challenge borders: between the aesthetic and political, individual and collective, past and future.

Created in contexts of erasure, persecution, and inequality, Latin art reaffirms that the image can be struggle, but it can also be healing, enchantment, and the possibility of another world.