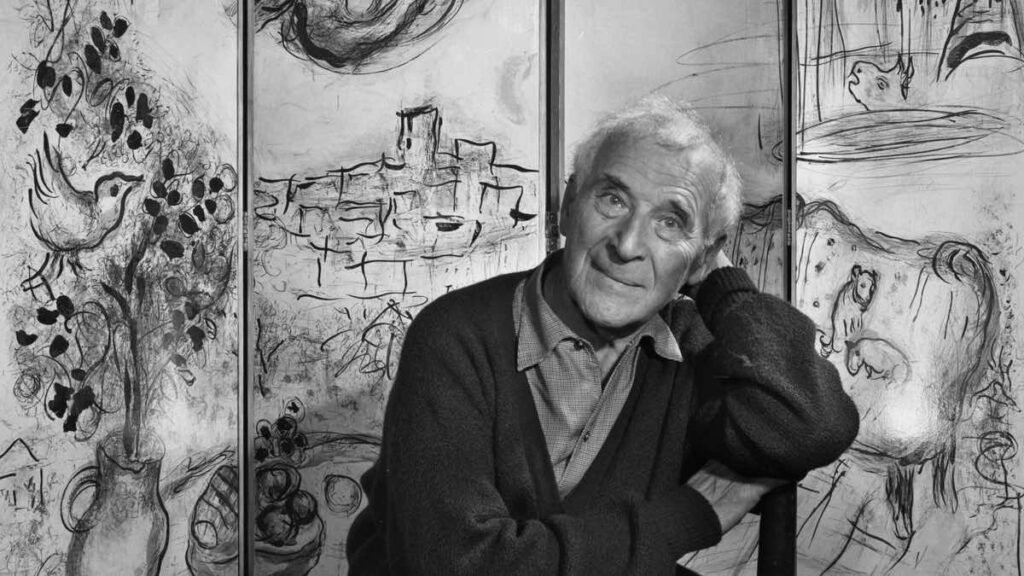

Marc Chagall (1887–1985) always painted as if crossing two universes. On one side, the memory of Vitebsk, his Jewish village in Tsarist Russia, filled with folk tales, synagogues, and the modest life of peasants. On the other, Paris of the avant-gardes, where Cubists, Fauvists, and Futurists reinvented themselves at the speed of the 20th century.

Marc Chagall did not confine himself to any of these schools but drew from them what suited him. With that, he built a unique language in which oxen, violinists, and lovers fly over villages, and everyday life becomes fable. His work is defined less by adherence to the aesthetics of the new and more by fidelity to memory as an inexhaustible source of poetry.

Memory as Artistic Matter in Marc Chagall

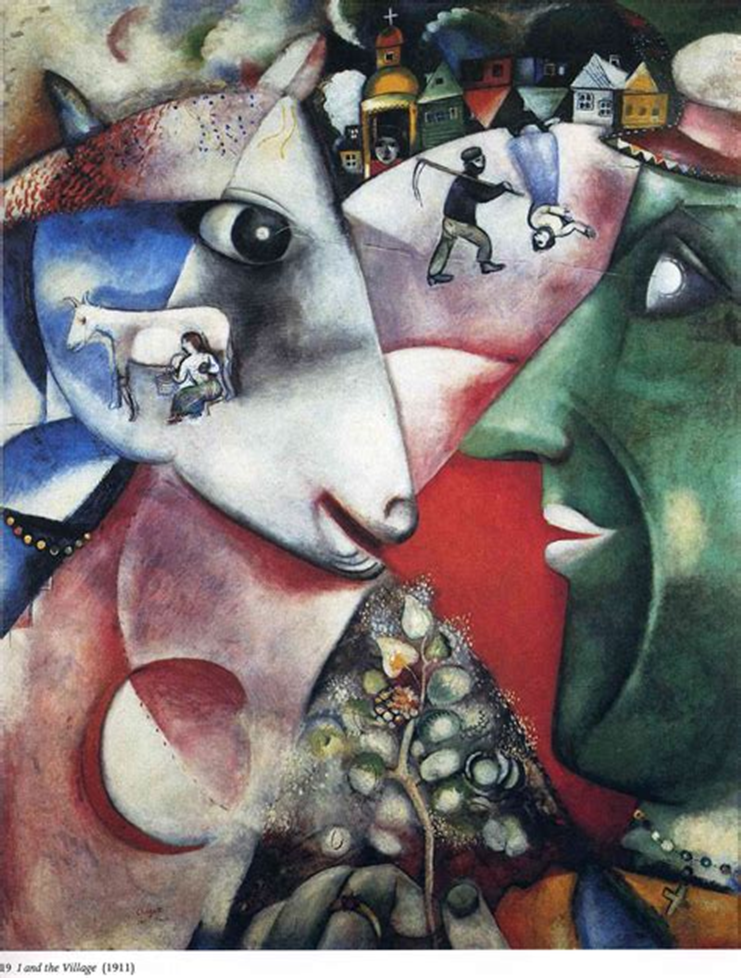

From early on, his painting revealed this stance. In I and the Village (1911), his hometown appears as a mosaic of recollections. There is no central perspective or linear narrative. The painting is simultaneous: peasants, houses, animals, and faces overlap like fragments of memory. The result is not faithful description but fabulation. Chagall transforms memory into painting and, in this process, blends reality and imagination. His art declares that true reality is not what the eyes see but what memory insists on preserving.

The Bible and The Poetry of Resistance

The Bible also played a central role in his path. Chagall did not treat it as dogma but as ancestral poetry. In his biblical series, and especially in the crucifixions painted between 1938 and 1943, Christ appears not as a devotional figure but as a symbol of Jewish suffering under Nazism.

The appropriation of Christian iconography by a Jewish artist creates a powerful inversion: the sacred becomes a political metaphor, both denunciation and hope.

The use of intense color and the visionary atmosphere of these paintings translate an attempt to give form to a world in crisis without abandoning the mythical dimension.

The Universal Legacy of Marc Chagall

During his exile in the United States, Chagall expanded this imagery into other mediums. Stained glass, murals, and stage designs showed that his painting could reach beyond canvas and occupy public spaces on a monumental scale. Even in these large works, his lyrical universe remained intact.

Floating figures, violin-playing animals, and lovers suspended in the air persisted as hallmarks of a poetics of childhood and memory. Thus, his work found a place both at the UN and in the ceilings of the Paris Opera without losing its village roots.

What makes Marc Chagall unique is his refusal to separate the mythical from the everyday. His flying characters are not superficial metaphors but the persistence of a gaze that refuses to accept the weight of gravity. There is an intimate resistance in his work, a rejection of modern banality through dream and memory.

While many of his contemporaries defined themselves through rupture and shock, Chagall chose continuity, imagination, and memory as survival strategies. That is why his work remains current: it does not belong solely to the time of the avant-gardes but to an inner space where reality and dream never fully disconnect.