Montage in Brecht is, above all, a principle of shock. Unlike the continuous and harmonious narrative of Aristotelian drama, Brechtian dramaturgy is built as a succession of independent scenes that do not seek to merge organically. Each episode has autonomy and carries within itself a lesson or contradiction, but it is in juxtaposition that it acquires full meaning.

The audience, instead of being guided by psychological progression, must actively make the effort to connect the fragments. What is seen in contrast is not a reconciled whole but the friction between parts.

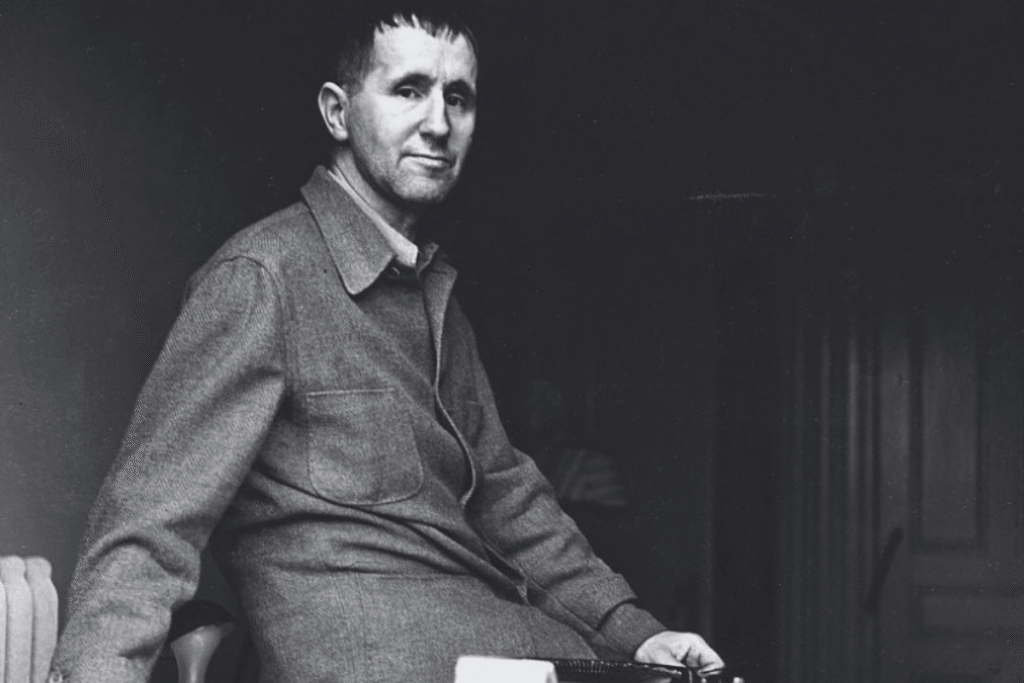

Brecht and the impact of theatrical montage

This technique has roots in Eisenstein’s montage cinema, which understood editing as a shock that generates ideas. Brecht translated this logic to the stage. The abrupt leap from one scene to another, the contrast between song and dialogue, the interruption of narrative by placards or commentary shift the spectator’s gaze.

What emerges is the historicity of the staged event. Nothing appears natural or inevitable but rather as the product of contending forces. Thus, theater becomes pedagogical, showing that reality is constructed and therefore can be transformed.

Contraposition also appears in acting. Brecht developed the “not, but” technique, in which the actor presents the audience with one choice while hinting at another possibility. Instead of embodying a closed psychological fate, the performer reveals a bifurcation.

The effect is critical distancing: the audience sees not only the action but also the alternative that was rejected. This exposure of possible paths reinforces the historical and non-natural character of human conduct.

Examples of Montage in Brecht

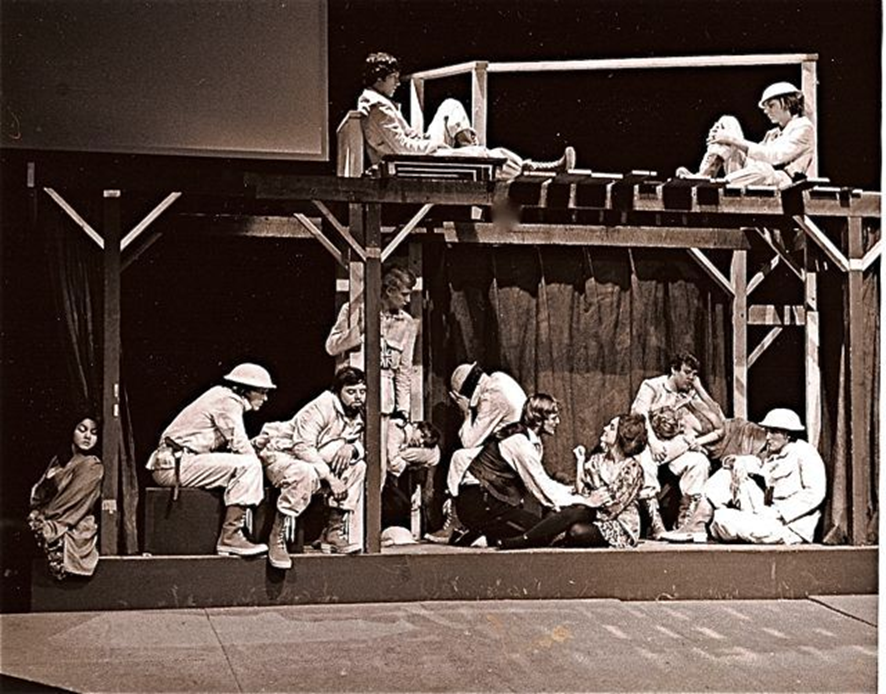

In his plays, the episodic structure highlights the method. In Mother Courage and Her Children, each scene shows the protagonist reacting to a situation of war. There is no psychological progression toward redemption but rather repetitions that expose the destructive logic of conflict.

Montage places contradictory episodes side by side, such as the loss of each child under different circumstances. The result is not catharsis but estrangement. The audience does not comfortably identify but is compelled to compare, notice patterns, and ask about causes.

This logic of contraposition does not seek synthesis. Brecht does not intend to pacify opposites but to expose them. The scene does not reconcile emotion and reason but instead lays bare the fracture. Hence the use of songs that interrupt the action, sometimes ridiculing, sometimes commenting on events.

The spectator is invited to judge, not to dream. In this sense, montage is also political: it shows that reality consists of social contradictions and that understanding them is a necessary step toward transformation.

The Critical Legacy of Brechtian Montage

In Brechtian contraposition, theater ceases to be illusion and becomes analysis. Each scene is a piece of an argument that does not resolve but instead exposes itself in tension. What the audience sees is not narrative continuity but the fissure between fragments.

Out of this fissure arises the critical effect: the possibility of seeing the world as montage and, therefore, as something that can be dismantled and rebuilt.