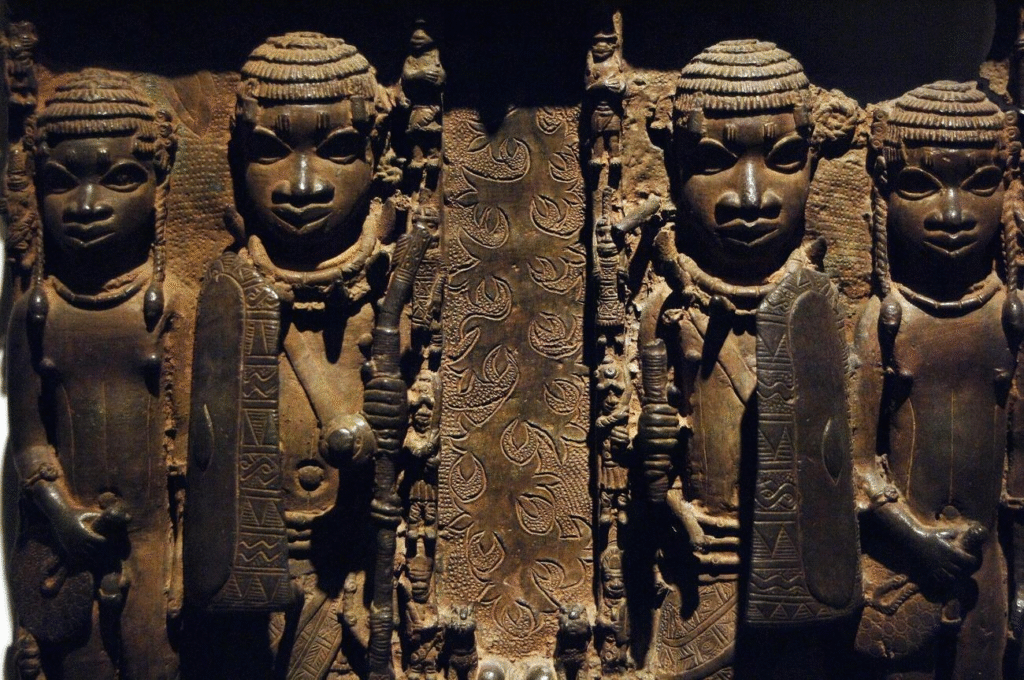

The so-called Benin Bronzes represent just one of countless examples of African art removed from original contexts.

These ritual objects, often depicting divine figures, ancestors, or spiritual forces, became cultural commodities in the West. Collectors valued them not only for material or aesthetic qualities but as symbols of power and faith by Africa.

By removing them from altars, palaces, and sanctuaries, age-old practices stopped, communities fractured, and collective memories shifted. What disappeared was not just the physical object but also the spiritual bond that gave it meaning.

During the colonial period, looting statuettes, bronzes, and masks became systematic. This pillage served a larger domination project, reducing religious practices and traditions to exotic curiosities for European collections. What expressed African peoples’ connection to the sacred transformed into military trophies, ethnographic specimens, or museum pieces.

The Western gaze cataloged, classified, and displayed these works as proof of distant otherness, stripping away their ritual depth. The violence existed not only in the act of taking but in redefining these objects’ nature: the divine became artifact, the sacred aesthetic.

The Fight for the Restitution of Art from Africa

The current debate on restitution brings this historical silencing back to the center of discussion. Demands for return extend beyond bronze, wood, or ivory sculptures to restoring dignity stolen from origin communities. These are stolen gods, not metaphorically, but as evidence of colonialism interfering with peoples’ care for spiritual symbols.

Returning them acknowledges past violence and looting while admitting that their presence in European museums reflects unequal power.

In this scenario, the role of digital platforms has been decisive. YouTube, among other networks, has become a space for public contestation and debate. Young people, researchers, African leaders, and members of the diaspora produce videos and visual essays that deconstruct colonial narratives still reproduced by cultural institutions. The circulation of these voices pressures museums to respond, questioning historical justifications that were accepted without challenge for decades.

The return of the artworks does not end the discussion but opens up the possibility of rethinking modes of cultural circulation, forms of international cooperation, and the role of the museum in the present. Thus, the stolen gods remind us that the history of art cannot be separated from the history of colonial violence. Acknowledging this past is a condition for imagining a future in which memory, justice, and the sacred are not treated as assets to be accumulated, but as rights to be respected and shared.