Minimalist art, characterized by geometric precision and formal objectivity, found in Dan Flavin one of the most unique and radical voices of the 20th century. His work challenges the boundaries between sculpture, architecture, and light, revealing that simplicity can hold emotional depth and conceptual strength.

The movement emerged in New York in the 1960s as a response to abstract expressionism, rejecting its gestural subjectivism in favor of a more direct and impersonal language. Flavin, born in 1933, lived through this moment intensely and found in industrial materials and light a new path for art.

Dan Flavin: Building a Radical Visual Vocabulary

Before dedicating himself to art, Dan Flavin had a religious background, served in the Air Force, and worked in museums such as the Guggenheim and MoMA. These environments brought him closer to other key figures of minimalism and pushed him to develop his own language.

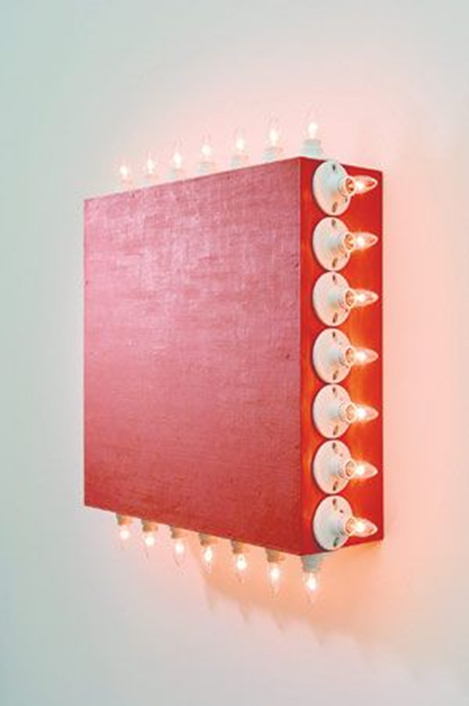

Early in the 1960s, he started the Icons series, composed of panels illuminated with fluorescent lamps. These early works showed his intention to transform light into sculptural matter.

From 1963 onward, Flavin exclusively used fluorescent tubes in his works. The piece The Diagonal of Personal Ecstasy marked this turning point by presenting a yellow light tube diagonally across a white wall.

He abandoned traditional supports and transformed industrial light into his main tool of visual expression. Colors like blue, green, red, and ultraviolet began to compose installations that profoundly altered the perception of exhibition spaces.

Art, Space, and Viewer: A Sensory Experience

Flavin’s works did more than illuminate. They created what the artist called “situations” — spatial experiences involving the viewer’s body. Art ceased to be an object and became an environment.]

Walls, corners, and floors became part of the work. This dissolved the boundary between sculpture and architecture. Thus, minimalist art gained a new dimension. The visitor’s physical interaction became essential. Their perceptual interaction was also part of the creation.

There were no metaphors or hidden narratives. What Flavin proposed was a direct relationship. This was between the artwork and the audience. The minimal use of materials revealed a maximum experience. This precise simplicity was far from limiting. It expanded the possibilities of perception. It made art accessible and immersive. At the same time, it was also challenging.

Minimalist Art: A Legacy That Transcends Time

After his death in 1996, the Dia Art Foundation transformed an old firehouse in Bridgehampton, New York, into the Dan Flavin Art Institute. Today, the space is an international reference for those seeking to understand the paths of minimalist art. Many contemporary artists working with light, sound, and spatiality recognize Flavin’s influence as fundamental.

His work remains relevant by questioning the very foundations of art: what it means to see, to perceive, to stand before something.

By reducing art to its essentials — light, color, and space — Dan Flavin revealed that even a simple fluorescent tube can teach us new ways of contemplation and presence in the world.