Abstract art has always been in dialogue with architecture. Not just through visual affinity between geometric forms, but through a shared pursuit: the sensitive ordering of space and the construction of meaning through structure.

When we observe the work of artists such as Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, and Lygia Clark, we realize that painting extends beyond the two-dimensional plane. It becomes a spatial experience.

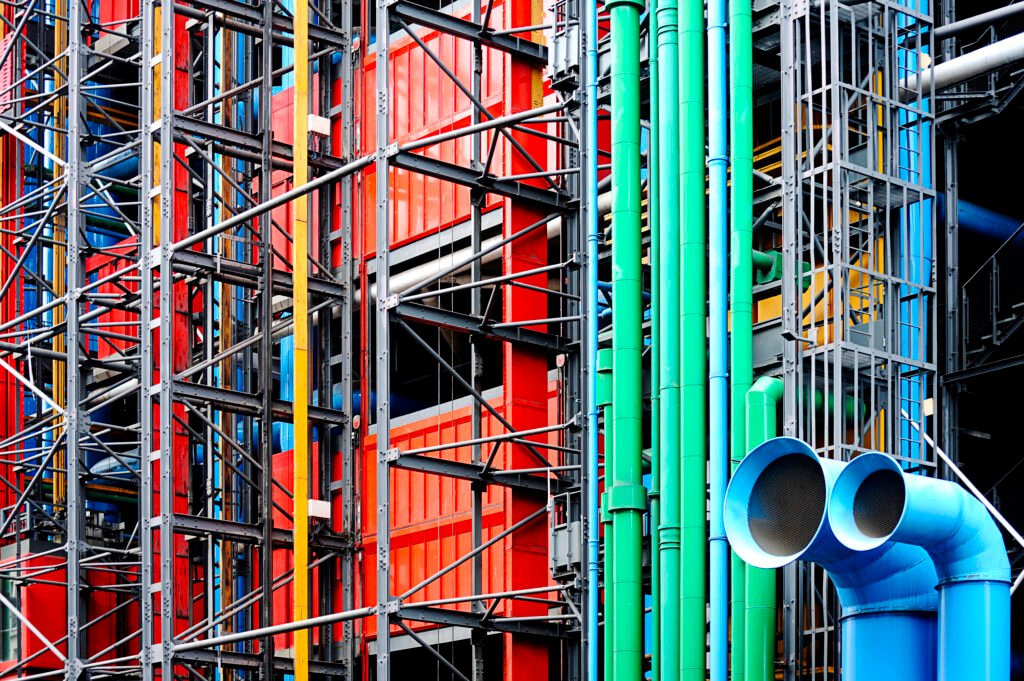

This relationship is not merely aesthetic. It represents a deep construction between pictorial gesture and the organization of the world. Geometric abstraction, in this sense, plays an architectural role, both in formal composition and in the way it reflects on the body, the environment, and the interaction between elements.

This intersection between art and architecture remains relevant today and reveals new layers of meaning to those who wish to buy abstract art with intention and awareness.

Geometry as language: from painting to space

Kazimir Malevich, in developing Suprematism in the early 20th century, broke with all forms of representation. Instead, he proposed the square as an absolute symbol of the autonomy of art.

For him, pure form could communicate an inner universe free from narrative function. His iconic work Black Square (1915) not only caused an aesthetic rupture, but also influenced generations of artists and architects in understanding form as a structure of thought.

Piet Mondrian followed a similar path in his search for balance and harmony. His compositions of straight lines, primary colors, and carefully proportioned spaces sought to translate the “universal spirit” through abstraction.

In his essay Plastic Art and Pure Plastic Art (1937), Mondrian claimed that art should accompany the spiritual evolution of humanity by ceasing to represent objects and instead building visual rhythms.

His work had a direct influence on the De Stijl movement. This movement inspired modernist architecture, including the works of Gerrit Rietveld and the Bauhaus school.

In Brazil, Lygia Clark elevated the relationship between abstract art and space to a new level. Beginning in the 1960s, her propositions moved beyond painting and into sensorial and bodily experiences.

Works such as the Bichos (1960) and Relational Objects (1970) transformed the structure of art into a mobile, articulated organism in which the viewer actively participates in the formation of the work. Geometry here is no longer static. It opens itself to action, to touch, to physical presence.

A study conducted by the University of São Paulo (Experience and Body in the Art of Lygia Clark, 2020) analyzes how the artist broke the separation between the art object and architectural space, creating a hybrid field of interaction.

To decorate, inhabit, and feel: Abstract Art as inhabitable space

The affinity between abstract art and architecture is not just historical. It remains alive in the ways people interact with visual works in both private and institutional settings. Choosing a piece of abstract art for decoration is not only an aesthetic decision, but a spatial one. An abstract painting can visually expand a room, create tension through lines, invite rest, or stimulate thought.

When considering the sale of abstract art for architectural interiors, integration between artwork and space is increasingly valued. Galleries and digital platforms now offer not just images but curatorial perspectives oriented toward the spatial experience of collectors.

Works that once lived within the white cube of the museum are now integrated into living rooms, concrete walls, and entrance halls, retaining their conceptual and visual power.

Furthermore, buying abstract art has become a gesture of conscious sophistication. By incorporating structural elements into interiors, art ceases to be an accessory and begins to function as a spatial organizer.

This is how form speaks: with the wall, with light, and with the moving gaze. Every line, color, or rectangular plane engages with the space in an almost architectural function.

In this sense, abstract art transforms the environment into a field of living experience. It creates rhythm, scale, pause, and flow. Its dialogue with architecture is not imitation but cooperation.

And that is why, even after more than a century, abstraction still questions us as if it had been created yesterday. Because form continues to speak. And when we listen closely, the entire space transforms.